May 26, 2022 — A transmissible, fatal cancer is an outlier in the world of animal diseases, but it’s a brutal reality for researchers and conservationists trying to save Tasmanian devils from extinction.

The first recorded cancers in devils were detected in 1996 by a photographer who noted strange growths on the heads of a group of wild devils he spotted. Follow up by wildlife authorities discovered the growths were a form of cancer. The cancer quickly spread throughout the population. The disease has since destroyed 80% of the population.

Devil facial tumor disease (DFTD) is a unique form of transmissible cancer that is passed from one devil to another through biting, a common behavior that takes place during feeding and mating. The vast majority of infected Tasmanian devils die within three to nine months of developing visible tumors. Primary tumors usually develop on the face or inside the mouth, and quickly grow into large tumors that metastasize to the internal organs.

After a period of rapid losses, a bit of good news for the devils was that young devils do not develop tumors and thus the population is sustained at low levels by young devils. More good news came when a few devils were observed to have natural tumor regressions. This has led to hope that the devil population evolved resistance to the tumors over time. Additionally, an experimental treatment was also able to induce tumor regressions, further showing that the devil immune system can kill tumor cells.

Unfortunately, a second form of the disease, devil facial tumor 2 (DFT2), was recently discovered among Tasmanian devils. DFT2 rose independently from the original disease (now designated DFT1), but both cancers are spread the same way. DFT2 originated in an isolated population of devils but recent reports suggest that the tumor is starting to spread out of the region.

When a cancer affects wildlife, there are systemic consequences that go beyond the loss of an individual. In the case of the massive loss of devils, the entire ecosystem is disrupted.

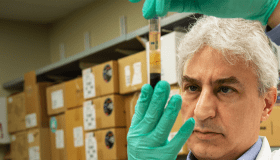

“The tumor creates a lot of problems that might not be apparent at first sight,” said Dr. Andy Flies, Senior Research Fellow at the Menzies Institute for Medical Research, University of Tasmania, and recipient of a Morris Animal Foundation-funded fellowship. “For example, Tasmania has abundant wildlife, which unfortunately leads to a massive amount of roadkill animals like wallabies – a favorite meal of devils. Older devils have more experience avoiding vehicles on roads but they’re the age group primarily affected by DFTD. Young devils don’t have experience with cars and often end up as roadkill themselves while trying to get an easy meal on the roads.

“Devil loss also affects other wildlife. For example, feral cats a major problem for small, native animals in Tasmania. Devils aren’t thought to actively hunt cats, but a recent study has shown that cat DNA is regularly found in devil scat. Keeping feral cat numbers down helps native animals, such as bandicoots, flourish. This is just one of the many downstream effects of DFTD.”

With all this bad news, it's tempting to feel disheartened and give up trying to find a solution. However, researchers like Dr. Flies are working hard to figure out a way to stop the disease. It’s not practical to use conventional cancer treatments, such as surgery or chemotherapy, in wildlife. But developing a cancer vaccine might be a way to treat large numbers of devils from developing the disease.

Dr. Flies’ research has been focused on achieving this ambitious goal. And the team has made great progress toward a vaccine that would be concealed in an edible bait.

There were and are many hurdles to clear on the road to creating a vaccine. Researchers first had to learn about the immune system of the devils as well as how the system reacts when encountering DFTD. Another hurdle was understanding the differences between DFT1 and DFT2. And then there’s been some trial and error with different anti-tumor strategies.

Dr. Flies collaborates with teams around the world (some of them also Foundation grant recipients), each working on a piece of the puzzle. Each day they race to find a solution that can help rebuild the devil population.

An additional benefit to the work is that the knowledge gained by working on the devil cancer problem might have applications in other species, including people. Dr. Flies noted that the strategies they used to develop a viable vaccine and the information they learned about the basic biology of the cancer could help other research teams.

The Foundation has funded four large scale research projects on the DFTD since 2014 and we’re getting closer than ever to a solution.

Through support from people like you, we can help people like Dr. Flies save our precious wildlife. Help us continue to move forward and Stop Cancer Furever.

HELP ANIMALS TODAY

Learn more about our wildlife studies and what you can do to help our wild animal friends live longer, healthier lives!